Robots Aren't the Problem: It's Us

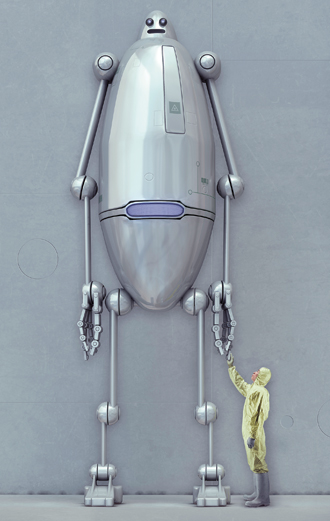

Swikar Patel for The Chronicle Review

Everyone has an opinion about technology. Depending on whom you ask, it will either: a) Liberate us from the drudgery of everyday life, rescue us from disease and hardship, and enable the unimagined flourishing of human civilization; or b) Take away our jobs, leave us broke, purposeless, and miserable, and cause civilization as we know it to collapse.

The first strand of thinking reflects "techno-utopianism"—the conviction that technology paves a clear and unyielding path to progress and the good life. George F. Gilder's 2000 book Telecosm envisions a radiant future of unlimited bandwidth in which "liberated from hierarchies that often waste their time and talents, people will be able to discover their most productive roles." Wired's Kevin Kelly believes that, although robots will take away our jobs, they will also "help us discover new jobs for ourselves, new tasks that expand who we are. They will let us focus on becoming more human than we were."

RELATED ARTICLES

The technology critic Evgeny Morozov dubs today's brand of technology utopianism "solutionism," a deep, insidious kind of technological determinism in which issues can be minimized by supposed technological fixes (an extreme example he gives is how a set of "smart" contact lenses edit out the homeless from view). We latch on to such fixes because they enable us to displace our anxieties about our real-world distress, the New Yorker staff writer George Packer explains: "When things don't work in the realm of stuff, people turn to the realm of bits." Morozov points to a future in which dictators and governments increasingly use technology (and robots) to watch over us; Packer worries about "the politics of dissolution," the way information technology erodes longstanding identities and atomizes us.

On the other side stand the growing ranks of "techno-pessimists." Some say that technology's influence is greatly overstated, seeing instead a petering out of innovation and its productive forces. According to the George Mason University economist Tyler Cowen, for example, America and other advanced nations are entering a prolonged "great stagnation," in which the low-hanging fruits of technological advance have largely been exhausted and the rates of innovation and economic growth have slowed. Robert J. Gordon, an economist at Northwestern University, adds additional statistical ammunition to this argument in his much-talked-about paper, "Is U.S. Economic Growth Over?" Computers and biotechnology have advanced at a phenomenal clip, he demonstrates, but they have created only a short-lived revival of growth. Today's innovations do not have the kind of world-shaking impact that the invention of modern plumbing or the introduction of self-propelled vehicles did (they're "pipsqueaks" by comparison)—and they are more likely to eliminate than to add jobs.

Another techno-dystopian strand sees the "rise of the robots" as a threat not just to blue-collar jobs but also to knowledge work. "To put it bluntly, it seems that high-skill occupations can be mechanised and outsourced in much the same way as car manufacturing and personal finance," Tom Campbell, a novelist and consultant in the creative sector, blogs, pointing to commercial software that already analyzes legal contracts or diagnoses disease.

The dustbin of history is littered with dire predictions about the effects of technology. They frequently come to the fore in periods in which economies and societies are in the throes of sweeping transformation—like today.

During the upheaval of the Great Depression, the late Harvard University economist Alvin Hansen, often called the "American Keynes," said that our economy had exhausted its productive forces and was doomed to a fate of secular stagnation in which the government would be constantly called upon to stoke demand to keep it moving. Of course we now know from the detailed historical research of Alexander J. Field that the 1930s were, in the title of his 2008 paper, "The Most Technologically Progressive Decade of the Century," when technological growth outpaced the high-tech innovations of the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s.

As the late economist of innovation Christopher Freeman long ago argued, innovation slows down during the highly speculative times leading up to great economic crises, only to surge forward as the crisis turns toward recovery. While data are scanty so early into our current recovery cycle, a new, detailed report from the Brookings Institution shows a considerable uptick in patented innovations over the last couple of years,

More than 100 years ago, during an earlier depression, H.G. Wells's The Time Machine imagined a distant future when humanity had degenerated into two separate species—the dismal Morlock, the descendants of the working class, who lived underground and manned the machines, and the ethereal Eloi, their former masters, who had devolved to a state of abject dependency. A little more than half a century later, Kurt Vonnegut's Player Piano depicted a world in which "any man who cannot support himself by doing a job better than a machine" is shipped off to the military or assigned to do menial work under the auspices of the government.

This either-or dualism misses the point, for two reasons.

The obvious one is the simple fact that technology cuts both ways. In their influential book Race Against the Machine, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, both at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, point out how technology eliminates some jobs but upgrades others. Similarly, Scott Winship, an economist with Brookings, recently noted in an article in Forbes that "technological development will surely eliminate some specific jobs." But the productivity gains from those developments, he added, "will lower the cost of goods and produce more discretionary income, which people will use to pay other people to do things for them, creating new jobs."

What economists dub "skill-biased technical change" is, in fact, causing both the elimination of formerly good-paying manufacturing jobs and the creation of high-paying new jobs. As a result, work is being bifurcated—into high-pay, high-skill knowledge jobs and low-pay, low-skill service jobs.

The second and more fundamental problem with the debate between utopians and dsytopians is that technology, while important, is not deterministic. As the great theorists of technology, economic growth, and social development Karl Marx and Joseph Schumpeter argued—and modern students of technological innovation have documented—technology is embedded in the larger social and economic structures, class relationships, and institutions that we create. All the way back in 1858, inGrundrisse, Marx noted: "Nature builds no machines, no locomotives, railways, electric telegraphs, self-acting mules, etc. These are products of human industry." Technological innovation, he went on "indicates to what degree general social knowledge has become a direct force of production, and to what degree, hence, the conditions of the process of social life itself have come under the control of the general intellect and been transformed in accordance with it."

In his landmark 1990 book on economic progress from classical antiquity to the present, The Lever of Riches, the economic historian Joel Mokyr also distinguisheshomo economicus, "who makes the most of what nature permits him to have," from the Promethean homo creativus, who "rebels against nature's dictates." He places emphasis, like Schumpeter perhaps, on human beings' underlying creative ability to mold technology by building institutions, forging social compacts, making work better, building societies. Technology does not force us into a preordained path but enables us, or, more to the point, forces us to make choices about what we want our future to be like.

We do not live in the world of The Matrix or the Terminator movies, where the machines are calling the shots. When all is said and done, human beings are technology's creators, not its passive objects. Our key tasks during economic and social transformations are to build new institutions and new social structures and to create and put into effect public policies that leverage technology to improve our jobs, strengthen our economy and society, and generate broader shared prosperity.

Our current period is less defined by either the "end of technology" or the "rise of robots" than by deep and fundamental transformations of our economy, society, and class structures. The kinds of work that Americans do have changed radically over the course of the last two centuries, particularly during major economic crises, like the Panic and Depression of 1873; the Great Depression of the 1930s; the Crash of 2008. Each shift has been hugely disruptive, eliminating previously dominant forms of employment and work, while generating entirely new ones.

In 1800 more than 40 percent of American workers made their livings in farming, fishing, or forestry, while less than 20 percent worked in manufacturing, transportation, and the like. By 1870, the share of workers engaged in those agricultural jobs had dropped to just 10 percent; during those same decades, the ranks of blue-collar manufacturing workers had risen to more than 60 percent.

That was not a smooth change, to say the very least. Rural people feared—often rightly—that their friends and family who were moving to the cities were dooming themselves to immiseration and brutal exploitation, working 16-hour days for subsistence wages. When labor began to organize for better conditions, management hit back hard—in some cases unleashing armed Pinkertons on strikers. The Panic of 1873 and the Long Depression that followed it began as a banking crisis precipitated by insolvent mortgages and complex speculative instruments, and it brought the entire economy to a virtual standstill. But the technological advances perfected and put into place during that decade of economic stagnation—everything from telephones to streetcars—created the powerhouse industrial cities that underpinned a vast industrial expansion.

The battles, and the terrible working conditions, continued well into the 1930s, when my father went to work in a Newark, N.J., factory at age 13. Nine people in his family had to work—both parents, both grandparents, and several siblings—to make one family wage. The Industrial Revolution had been going on for more than a century before a new social compact was forged—a product of worker militancy, enlightened self-interest on the part of owners and management, and pressure from the government—that brought safety, dignity, and security to blue-collar work. It was this compact that buttressed the great age of productivity in the post-World War II era. When he returned from the war, my father's job in the very same factory he had previously worked in had been transformed into a good, high-paying occupation, the kind we pine for today, which enabled him to buy a home and support a family.

But beginning around 1950, when Kurt Vonnegut was working for General Electric and writing Player Piano, the share of working-class jobs began to fall precipitously. It wasn't just automation that was doing it—our whole economy was shifting again, and our society was changing with it. There was the civil-rights movement and later the anti-war youth movement, feminism, and gay rights. People began to rebel against the enforced conformity of corporate life. A new ethos was bubbling up, in Haight-Ashbury and Woodstock through music and art and fashion, and in Silicon Valley with computers and high tech. Some economists began to talk about how the industrial economy was transitioning to a service economy; others, like the sociologist Daniel Bell, saw the rise of a postindustrial economy powered by science, technology, and a new technocratic elite. The pioneering theorist Peter Drucker dubbed it a "knowledge economy."

Almost a decade ago, in my book The Rise of the Creative Class, I called it a "creative economy," because creativity, not knowledge, has become the fundamental factor of production. Our economy uses technology, but it is not principally powered by it. Its motive force is creativity. Economic and social progress result from the interweaving of several distinctive, related strands of creativity: innovative or technological creativity, entrepreneurship or economic creativity, and civic or artistic creativity.

Our current economic circumstance is not simply the product of faceless technology; it is also informed and structured by socioeconomic class.

The key organizing unit of the postindustrial creative economy is no longer the factory or the giant corporation. It is our communities and our cities. Cities are the organizing or pivot point for creativity, its great containers and connectors. Unlike the services we produce, the technologies we create, or the knowledge and information that is poured into our heads, creativity is an attribute we all share. It is innate in every human being. But it is also social, it lives among us: We make each other creative. With their dense social networks, cities push people together and increase the kinetic energy among them. If the powerhouse cities of the industrial era depended on their locations near natural resources or transportation centers, our great cities today turn on the people who live in them—they are where we combine and recombine our talents to generate new ideas and innovations.

Like the Industrial Revolution, the rise of the knowledge-driven, creative economy has transformed the composition of the work force, with harrowing consequences. The picture is brutally clear: Working-class employment has declined by 50 percent in the last half century. Blue-collar workers made up 40 percent of the work force in 1980; they are just 20 percent of the work force today. In just the one decade between 2000 and 2010, the United States shed more than 5.7 million production jobs.

As the working class, like the agricultural class before it, has faded, two new socioeconomic classes have arisen: the creative class (40 million strong in the United States, roughly a third of the work force) and the even larger service class (60 million strong and growing, about 45 percent of the work force). If the creative class is growing, the service class is growing even faster. Last year the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics published a list of the fastest-growing occupational categories in the United States, projected out to 2020. Most of the top 10 were in the service sector. The two fastest-growing jobs, which are expected to grow by roughly 70 percent by 2020, were personal-care aides and home health aides. The former, which pays a median of just $19,640, will add more than 600,000 jobs; the latter, which pays $20,560, will grow by more than 700,000 jobs. There was only one clearly creative-class job in the top 10—biomedical engineer (an $81,540-a-year job).

Our current economic circumstance is not simply the product of faceless technology; it is also informed and structured by socioeconomic class. The creative class is highly skilled and educated; it is also well paid. Creative-class jobs average more than $70,000 in wages and salaries; some pay much more. Service-class jobs in contrast average just $29,000. The service class makes up 45 percent of the work force but earns just a third of wages and salaries in the United States; the creative class accounts for just a third of employment but earns roughly half the wages and salaries.

The divide goes even deeper. Add the ranks of the unemployed, the displaced, and the disconnected to those tens of millions of low-wage service workers, and the population of postindustrialism's left-behinds surges to as many as two-thirds of all Americans. That produces a much larger, and perhaps more permanent, version of the economic, social, and cultural underclass that Michael Harrington long ago dubbed "the other America." Only this time, it's a clear majority.

The effects of class extend far beyond our work and incomes to virtually every facet of our social lives. One class is not only wealthier and better educated than the other, its members are also healthier, happier, live in places with better services and resources of all sorts, and they pass their advantages on to their children.

To blame technology for all this is to miss the point. Instead of looking at technology as a simple artifact that imposes its will on us, we should look at how it affects our social and economic arrangements—and how we have failed to adapt them to our circumstances.

If nearly half the jobs that our economy is creating are low paid and unskilled and roughly two-thirds of our population is being left behind, then we need to create new and better social and economic structures that improve those jobs. That means more than just raising wages (though that has to be done), but actively and deliberately improving jobs. We did it before with factory jobs, like my father's.

We have to do it again, this time with low-wage, low-skill service work. That isn't charity or an entitlement—it's tapping workers' intelligence and capabilities as a source of innovation and productivity improvements.

My own research, and that of others, has identified two sets of skills that increase pay and improve work. Cognitive skills have to do with intelligence and knowledge; social skills involve the ability to mobilize resources, manage teams, and create value. These skills literally define high-wage knowledge work: When you add more of them to that work, wages go up. But here's the thing: When those skills are added to service work, wages increase at a steeper rate than they do in creative jobs.

Paying workers better also offers substantial benefits to the companies that employ them and to the economy writ large. While that may seem counterintuitive, detailed academic research backs it up. Zeynep Ton of MIT's Sloan School of Management argues that the notion that keeping wages low is the long way to achieve low prices and high profits is badly mistaken: "The problem with this very common view is that it assumes that an employee working at a low-cost retailer can't be any more productive than he or she currently is. It's mindless work so it doesn't matter who does it. If that were true, then it really wouldn't make any sense to pay retail workers any more than the least you can get away with."

In a study published in the Harvard Business Review, Ton finds that the retail companies that invest the most in their lowest paid workers "also have the lowest prices in their industries, solid financial performance, and better customer service than their competitors." As she has pointed out, the companies and jobs provide a powerful model that can be extended to other service-based jobs like those in hospitals, restaurants, banks, and hotels. Upgrading service jobs in this way, she says, "could help provide the kind of economic boost the economy needs."

We can't simply write off the tens of millions of workers who toil in dead-end service jobs, or the millions more who are unemployed and underemployed. The key to a broadly shared prosperity lies in new social and economic arrangements that more fully engage, not ignore and waste, the creative talents of all of our people.

Just as we forged a new social compact in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s that saw manufacturing workers as a source of productivity improvements and raised their wages to create a broad middle class to power growth, we need a new social compact—a Creative Compact—that extends the advantages of our emergent knowledge and creative economy to a much broader range of workers. Every job must be "creatified"; we must harness the creativity of every single human being.

I'm optimistic, even in the face of deep economic, social, and political troubles, because the logic of our future economic development turns on the further development and engagement of human creativity.

As in the past, it won't be technology that defines our economic future. It will be our ability to mold it to our needs.